Making LLM My Second Brain: Using Personal Blog as RAG with MCP Server

Hello! I’m Jeongil Jeong, a 3-year backend developer working at a proptech platform.

Recently, AI, especially LLMs (Large Language Models), has been gaining significant attention among developers. While “recently” might be a bit of an understatement given how much time has passed, AI technology is increasingly permeating developers’ daily lives and various industries. I’ve also been pondering how to leverage LLMs to boost productivity, enhance learning, and manage knowledge.

As one of those approaches, I’ve configured my experiences and rules to be accessible to LLMs using MCP (Model Context Protocol) Server, and I’d like to share this journey in this post.

Second Brain

Have you heard of Obsidian? Obsidian is a developer tool for note-taking and memo writing, similar to Notion or OneNote. It supports the Markdown format familiar to developers, stores files locally, and has a powerful linking feature and plugin ecosystem.

Why am I suddenly bringing up Obsidian? I believe one of the main reasons developers use Obsidian is to leverage it as a “Second Brain”.

Just search for Obsidian, and you’ll find articles like “How to Use Obsidian as Your Second Brain!” or “Building a Second Brain for Developers.” Many developers use Obsidian to systematically organize and manage their knowledge.

What is a Second Brain? It’s a system that externalizes the knowledge in your head for storage and management. Various tools like Obsidian, Notion, and Roam Research can be used to build a Second Brain.

Why Do People Want a Second Brain?

So why do people want a Second Brain?

Developers solve new problems every day, design complex systems, and use various tools and technologies. While much knowledge and experience accumulates in this process, it can easily be forgotten or underutilized without systematic management. Memories naturally fade over time. Of course, this applies not only to developers but to all professions.

The countless knowledge and experiences encountered during development—troubleshooting experiences, considerations in architecture decisions, conventions and rules, performance improvement know-how, organized learnings from study—these can all be organized in Obsidian, connected with links, and retrieved when needed, allowing developers to “externalize the knowledge in their heads”.

The first brain (your head) focuses on pondering new problems, while the second brain (Obsidian) takes on the role of storing past experiences.

But Obsidian Has Its Limitations

Like all tools, Obsidian has its downsides along with its advantages. The downside I saw in Obsidian as a second brain is that it’s passive.

Even if knowledge about what experiences I’ve had and how I solved problems is well-organized in Obsidian, the process of finding and utilizing it had to be manual.

For example, when facing a new problem, I had to open Obsidian and search with relevant keywords. Then find related notes from the search results, read them, and apply that content to the current problem.

“How did I solve this problem?” I’d think, then open the search bar and sift through various notes to find relevant content. The experience of wasting time digging through documents to find the convention document you organized—we’ve all been there, right?

Can We Create a Second Brain with LLM in the AI Era?

So is a non-passive second brain possible? While it was difficult before, I think it has become possible with the advancement of AI, especially LLMs (Large Language Models).

You’ve probably experienced ChatGPT, Gemini, or Claude remembering what you said and providing answers tailored to your situation. This is because LLMs can understand conversational context, remember previous dialogue content, and generate user-customized responses.

This is thanks to features like “Memory”, “Custom Instructions”, and “Projects” provided by LLM platforms. Internally, they’re divided into Short Term Memory and Long Term Memory, but let’s skip the details as they’re a bit off-topic.

Ultimately, the LLM remembers what you say and recalls what was discussed before. These features align quite well with the second brain role that developers want. The LLM remembers the knowledge and experience I’ve accumulated and applies it to new problems.

So if I consistently converse with an LLM on a specific platform, building up my knowledge and experience, can the LLM serve as my second brain?

Every time something happens, I ask ChatGPT or Claude, receive answers, and gradually the LLM accumulates my knowledge and experience. Later, when I need to use that knowledge, I ask the LLM, and it answers based on the knowledge and experience I’ve built up.

But can we really say we’ve completed a second brain this way?

This Approach Has Clear Limitations

1. Context Window Constraints

Context Window refers to the amount of text an LLM can process at once. Early GPT-4 was around 8,000 tokens, but recently models supporting 128k, 200k tokens or more have emerged. However, no matter how large the context window, there’s ultimately a limit.

When tokens are exceeded, the LLM starts forgetting previous conversation content. You’ve probably experienced this when having long conversations with ChatGPT or Gemini—previously discussed content gradually gets forgotten. This is due to Context Window limitations.

For example, you’ve probably experienced things like:

- “Always respond casually no matter what I say” → Initially complies well, but as the conversation lengthens, gradually switches to formal speech

Eventually, memories stored in Memory can end up not being delivered to the LLM due to Context Window limitations unless I mention them again.

2. Platform Lock-in

Another major problem is that “memories” accumulated on a specific platform are platform-dependent.

Memories accumulated in ChatGPT exist only in ChatGPT, and memories accumulated in Gemini exist only in Gemini. In other words, knowledge and experiences accumulated on a specific platform cannot be transferred to another platform. If you’re chatting with ChatGPT and ask “What did I say in Claude?” ChatGPT can’t know.

What if, after using ChatGPT for a year and diligently building up Memory, ChatGPT changes its paid version policy, performance drops, a better model appears on another platform, or you need to switch to Claude or Gemini for other reasons?

Despairingly, you have to rebuild Memory from scratch on the other platform.

Developers are accustomed to managing dependencies. When dependencies on libraries, frameworks, or specific cloud services arise, we try to manage and minimize them. Similarly, LLM platform dependency becomes something that needs to be managed.

Your knowledge gets locked into a platform.

3. Can It Be Solved with Prompts?

So to avoid lock-in, could I just prepare specific prompts and paste them every time I start a conversation on a new platform?

Actually, many LLM platforms provide Custom Instructions or prompt template features. This can solve the problem to some extent, but it has some issues.

Related to point 1, prompts that are too long eventually won’t be remembered due to Context Window limitations.

Also, knowledge for creating a second brain, like personal experiences, accumulates over time. When hundreds or thousands of notes and experiences pile up, it becomes impossible to fit them all in a prompt. Moreover, pasting prompts every time you start a new session is cumbersome. There’s also the cost issue. LLM platforms generally measure usage based on token consumption. This can lead to cost problems.

Attempts to Overcome LLM Limitations

This problem isn’t actually limited to second brain-related issues. Context Window problems, Memory, and cost issues are common challenges that any place utilizing AI must face.

These issues have been raised since the early days of LLMs. However, when there’s a problem, there are always various attempts to overcome it. A prime example is RAG.

RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation)

What is RAG? RAG is a methodology where the LLM retrieves information from an external knowledge base to generate answers. It’s actually a method we use at my company too.

Rather than the LLM storing all knowledge internally, documented knowledge is embedded and stored in an external knowledge base like a vector DB, and when the LLM receives a question, it searches for related information from the external DB using similarity-based search and includes it in the prompt to generate an answer.

What is embedding? It’s the process of converting text data into vectors (arrays of numbers). This allows the meaning of text to be expressed numerically, enabling applications like similarity search. Since this is a bit off-topic, let’s skip it.

- Retrieval: Search for documents related to the user’s question in an external database or vector DB.

- Augmentation: Combine the retrieved relevant information with the user’s question and deliver it to the model.

- Generation: The model generates the final answer based on the provided information.

These steps are followed. This allows Context Window limitations to be somewhat overcome, prevents hallucinations, and enables utilization of up-to-date information.

This methodology is utilized by many companies and developers. For example, companies can store their own documents, wikis, customer support materials, etc. in a vector DB and configure the LLM to utilize this when answering customer inquiries.

Thinking about past experiences searching StackOverflow makes this easy to understand. When developers faced new problems, they would search for related questions and answers on StackOverflow to solve problems. RAG is similar to having the LLM automatically perform this search process.

Before LLM platforms provided features like internet search, RAG construction was more common than it is now. This is because models only know up to the knowledge they were trained on, making it difficult to reflect the latest information. By storing the latest information in a vector DB through RAG and allowing the LLM to utilize it, up-to-date information can be reflected.

However, with LLM performance rising sharply now and LLM platforms releasing models capable of web search, I think the necessity of RAG has somewhat decreased.

But RAG is still useful when specific domain knowledge or personalized knowledge needs to be utilized. Also, because web search doesn’t always provide perfect answers, I think it can be important to provide verified information through RAG.

RAG also has limitations. Building and maintaining a vector DB requires cost and effort, and retrieved information may not always be accurate or highly relevant. There’s also the problem of needing to continuously update the vector DB data.

Even considering these aspects, I think RAG is one of the powerful methodologies for overcoming LLM limitations. Of course, there may be better methodologies I don’t know about, but as far as I know, RAG seems to be the most widely known and utilized methodology.

MCP Server: The Real Solution for Second Brain

Since I develop and operate RAG at my company, I suddenly had this thought:

“If the LLM could freely access documents on my personal blog and operate like RAG, couldn’t it really be utilized as a second brain?”

Make the LLM appropriately judge and find related posts from my blog to use in answers every time I query it. Make it operate like my personal RAG. That way, I could get reasoning and answers based on my own experiences and knowledge.

However, directly building and operating a RAG Server is cumbersome. It requires a lot of effort like building a vector DB, embedding documents, and implementing search logic. I didn’t want to do that.

But there was a way to make my blog freely readable and utilizable by the LLM without going through such cumbersome methods. That’s using an MCP (Model Context Protocol) server.

Of course, other people have already tried methods like this, and there may be open-source projects that can easily build this. However, since I wanted to experience building an MCP server myself, I decided to build it myself rather than looking for open-source, so please just refer to the core idea in this post.

What is MCP (Model Context Protocol)?

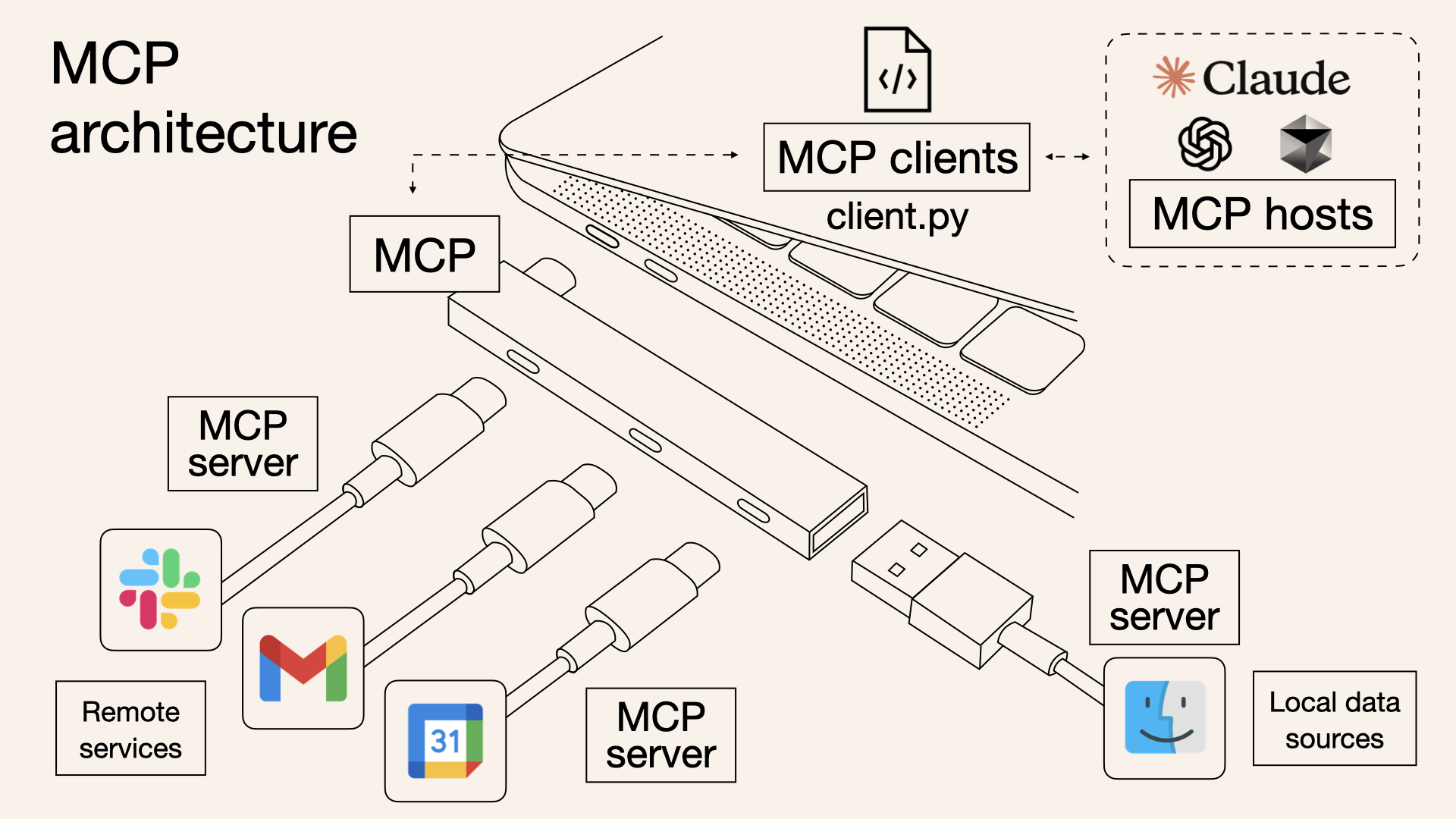

MCP is a standardized protocol that allows LLMs to access external knowledge sources. Simply put, you can think of MCP as a common interface that allows LLMs to communicate with the outside.

When you search for MCP, it’s described as acting as the hands and feet of the LLM. I think this expression is accurate because it provides the LLM with methods to access external tools.

For example, if you create an MCP server that accesses a MySQL database, the LLM can access MySQL through the MCP server when needed to read and write data. In fact, various database MCP servers like MySQL, PostgreSQL, and SQLite are publicly available in the official MCP server list.

So how can MCP solve the second brain problem? It’s simpler than you think. I just need to create an MCP server that provides access to my personal development blog.

This way, it’s platform-independent because it can be used with all LLMs that support MCP. Whether ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, or a company’s own LLM—as long as they can utilize MCP, they can access my blog.

Also, because it operates like RAG, it somewhat overcomes Context Window limitations. Since the LLM searches for and retrieves related posts from my blog, even if there are hundreds of posts on the blog, it can just retrieve and use a few necessary ones.

And it becomes a permanent knowledge repository. The knowledge and experiences accumulated on my blog remain intact even if platforms change, and stay even if conversations are deleted. I can retrieve them whenever needed.

Another big advantage is that because I directly operate the MCP server, I can manage knowledge and experiences in the way I want. Just by modifying or adding blog posts, I can easily update my second brain.

This also has the advantage of making me unknowingly update my blog consistently. If it becomes a knowledge repository that the LLM refers to, I’ll update it more often. 😊

This way, I think the LLM can truly be utilized as a Second Brain.

Like Obsidian, organizing and storing knowledge, but with the LLM actively finding, connecting, and applying it, while also being platform-independent and permanently maintained.

So I Built It

An MCP server that allows Claude Code to directly read and utilize my development blog (jeongil.dev).

From now on, I’ll write about how I actually built the MCP server and the specific implementation process.

llms.txt: Standard Format Readable by LLMs

When I decided to create an MCP server, the first thing I pondered was “How will the LLM read the blog content?”

I thought about scraping HTML pages via HTTP, but this had inefficient aspects.

HTML has more unnecessary tags and style information than markdown files, which could interfere with the LLM grasping the core content. Also, if the blog structure changed, the MCP server code would need to be modified, which was cumbersome.

That’s when I learned about the existence of the llms.txt standard.

What is llms.txt?

llms.txt is a standardized way for websites to introduce themselves to LLMs. If robots.txt is a file for search engine crawlers, llms.txt is a file for LLMs.

If you organize the site’s key information in markdown format at the /llms.txt path, the LLM can understand and utilize that site.

Why I Chose llms.txt

The Power of Standardization

Many sites had already adopted llms.txt. LLMs like Claude and ChatGPT also understand this standard. It was attractive that the LLM could immediately understand my blog without separate explanation.

Simplicity

Just one markdown file is needed. No complex JSON schema, no separate metadata needed. In a Hugo blog, just adding one

static/ko/llms.txtfile was enough.Flexibility

When new posts are added to the blog, just update llms.txt. No need to touch the MCP server code. Automation is also possible by just adding an llms.txt generation script to the Hugo build process.

My Blog’s llms.txt Structure

Previously, I was using Velog as my personal development blog. However, Velog didn’t support llms.txt, and customization was difficult. So I decided to introduce llms.txt while migrating my blog to Hugo + GitHub Pages.

Of course, since Obsidian also provides an MCP server, there was a method to use Obsidian, but connecting Obsidian to GitHub Pages was cumbersome, and I wanted to catch both rabbits—a development blog and a personal knowledge repository—so I chose to introduce llms.txt to a personal blog made with Hugo + GitHub Pages.

As I revealed in the post I wrote when migrating the blog to GitHub Pages, one of the core goals of the blog migration was introducing llms.txt.

Hugo is one of the most popular open-source static site generators. Hugo generates static websites based on markdown files. Files placed in the

staticfolder are copied as-is during build and included in the final site. So just adding astatic/ko/llms.txtfile was enough to easily provide llms.txt.

Being Go-based, the build speed is very fast, and various themes and plugins are supported, making customization easy. Also, there are various themes, so I quite liked the design. Integration with GitHub Pages is also easy, making deployment simple.

After migrating the blog to Hugo + GitHub Pages, creating llms.txt became simple.

The next thing I pondered was “How can I make it easy for the LLM to find what information?” when creating llms.txt.

I could just list all posts, but then the LLM would have difficulty finding the information it wants. So I divided them into two categories based on the nature of the information.

Documentation (Development Guidelines)

This category collects rules, conventions, and principles agreed upon by the team. I gathered documents about “How should we develop?” here.

Coding conventions, Git workflow, architecture principles, API design patterns, testing strategies, database rules, etc.

For example, when Claude Code creates a new API, if I say “Design and implement the API while following my development rules,” Claude Code searches Documentation and writes code by referring to the API design principles and coding conventions I’ve organized.

Tech Blog (Hands-on Experience)

This category collects problems I actually encountered and the resolution process. It’s a record of things like “How did I solve this problem in the past? What experiences have I had before?” Specifically, I categorized it as follows:

- Backend: HikariCP Deadlock, Spring Batch Chunk transition, etc.

- Infrastructure & DevOps: Migration from Docker Compose to Kubernetes, ArgoCD introduction, etc.

- Architecture & Design: Transition from MSA to Multi-Module, multi-module integration, etc.

- Development Culture: Git Flow improvement, code review culture establishment, etc.

Of course, there’s a bit more, but these are the representative categories.

By separating “rules” and “experience” this way, the LLM can accurately find information suited to the situation. This is why I wanted to include development rules and similar documents in my development blog.

Previously, with Velog, it was difficult to simultaneously manage documents and blog posts. Also, documentation tools like Mintlify are optimized for documentation and support llms.txt, but weren’t suitable for managing blog posts together.

But after migrating to Hugo, I could include both documents and blog posts, and clearly distinguish them in llms.txt.

The full content of llms.txt can be found at jeongil.dev/ko/llms.txt.

Implementation: Creating the MCP Server

Since I explained what MCP is above, let me now talk about how I actually built it.

Technology Stack Selection

Why I Chose FastMCP

When creating the MCP server, I chose FastMCP instead of the official MCP SDK.

This is because the concise API provided by FastMCP seemed to enable faster development.

| |

FastMCP Advantages:

- Decorator-based API (Flask/FastAPI style)

- Automatic schema generation (just write docstrings)

- Type safety (Pydantic integration)

- 50%+ code reduction

Project Structure

Initially, I thought about throwing all the code into one file. Since it’s a simple project. But thinking about the possibility of future expansion, I separated concerns.

my-tech-blog-mcp-server/

├── src/

│ ├── server.py # MCP server main logic (Resources, Tools, Prompts definition)

│ └── llms_parser.py # llms.txt parsing and search (HTTP requests, parsing, search)

├── run.py # Server execution entry point

├── requirements.txt # Dependencies

└── install.sh # Automated installation scriptWhy divide it like this?

llms_parser.py: Data layer that fetches and parses llms.txtserver.py: Service layer that exposes data according to MCP protocol

If I later want to use a different data source (Notion, Obsidian, etc.) instead of llms.txt, I just need to replace llms_parser.py. No need to touch server.py.

1. Implementing the llms.txt Parser

First, I created a module to fetch and search llms.txt.

| |

Key points:

- Async HTTP requests with

httpx(MCP server operates asynchronously) - Performance optimization with memory caching (llms.txt doesn’t change often)

- Simple string matching for search (YAGNI principle - start simple)

You can check the full detailed code at my GitHub repo.

2. Implementing the MCP Server

With the parser ready, it’s time to create the MCP server. It’s really simple with FastMCP.

| |

MCP has three main concepts.

1. Resources - Read-only data

| |

The LLM reads this when wondering “What’s in the entire blog?” Docstrings automatically become descriptions, so no separate schema writing is needed.

2. Tools - Functions the LLM can execute

| |

If you say “Find Kubernetes-related experience,” the LLM automatically calls search_experience("kubernetes"). I don’t need to command it.

3. Prompts - Reusable templates

| |

If you make frequently used question patterns into templates, you don’t need to input long prompts every time.

That’s all there is to FastMCP. Just attach decorators and you’re done. The documentation is so good that once you try it, you’ll realize it’s really easy to configure.

Before implementing the MCP server, I thought it would be complex, but I was surprised at how simple it was. Of course, there’s a lot to study in terms of detailed technology, but the implementation itself was really simple.

For detailed implementation methods and code, please refer to the resources below:

3. Installation Automation

Now the MCP server code is all written. But setting it up in a new environment every time was annoying. I use Claude Code in multiple environments—company MacBook, personal MacBook, desktop, etc. Setting up the MCP server every time was annoying, so I made an installation script.

One-line installation

| |

The script automatically:

- Creates Python virtual environment

- Installs dependencies (

fastmcp,httpx,pydantic) - Registers MCP server with Claude Code

Just restart Claude Code and it’s ready to use. What used to take 10 minutes to set up a new environment was reduced to 1 minute.

For the detailed script, check Github Repo - install.sh if you’re curious.

Actual Usage Results

After building the MCP server and connecting it to Claude Code, I felt it could really serve as a second brain better than I thought.

The above is just one example, but Claude Code immediately identified problems I encountered in the past from my blog and distinguished them by year.

Later, when I said “Find and summarize posts about HikariCP Deadlock from my blog,” it immediately found and summarized them.

Also, when I said “Review this code according to my development rules,” it reviewed the code by referring to coding conventions and API design principles from my blog.

Results and Effects

Now I don’t need to explain my situation or rules every time when collaborating with AI Agents. I just need to say “Check the development rules in my blog and review if there are any shortcomings in the current code.”

Also, I don’t need to search for past events myself—the AI finds them from my blog.

This way, as long as I keep good records, the AI can fully serve as my second brain.

Right now, my development blog only has experiences and rules, but for example, if I add a space to manage future tasks, the AI could also manage my schedule and to-dos.

When I ask “What do I need to do today?”, the AI checks my schedule and to-dos and tells me.

Through the MCP server, my second brain becomes not passive but actively helps with my work, and the more I record, the better it understands me and can reason.

It gives advice based on experience, warns me about mistakes I often make, and consistently maintains rules.

I really got to experience what a “second brain” is. It might sound like an exaggerated expression saying it repeatedly like this, but when you actually use it, it really feels that way.

What I Learned

1. Need to Organize Well

A very big and clear reason to write a blog has been added. Previously, it was simply a space to organize my experiences and a space to reflect on experiences while writing.

However, as the LLM became able to read and utilize my blog, the blog became a huge asset where AI utilizes my experiences and knowledge in real-time.

I haven’t written many blog posts, but I had organized experience-related parts, and while thinking about making an MCP server, I felt so glad I had written them down.

However, to utilize it well as a second brain, it needs to be well organized. Posts that aren’t properly organized are difficult for AI to utilize, and in some cases can give wrong information or cause hallucinations.

That could actually interfere with collaborating or utilizing AI. The importance of documentation is emphasized once again here. I felt once more that the ability to properly organize and record is a very important capability for developers.

I also realized again that if you record and organize well, it becomes a huge asset. Thinking that its value will grow even more in the future made me resolve to record and organize more diligently.

2. Context is Important for AI Collaboration

LLMs are smart, but without context, they only speak in generalities. They can also give wrong information. Therefore, I think if you inject context that you’ve verified in advance, the AI becomes your personal expert.

- My past experiences

- My development rules

- My architecture decisions and considerations

I think such context is necessary to receive more suitable and useful advice for me. Previously, I would add such documents to .claude in CLAUDE.md or as documents in skills.

I also did work to reduce token amount by separating into skills because the amount in CLAUDE.md got too large. [Have I Embraced the Future? - How to Collaborate with Developer AI Coding Tools]

But as documents increased, management became difficult, and updating them every time was cumbersome.

Also, common rules across multiple projects had to be added for each project every time.

By introducing the MCP server, all these problems were solved. My blog became my context repository, and the MCP server provides it to the LLM in real-time.

3. The Usefulness of Second Brain

When collaborating with AI Agents, role division became clear. I focus on the decision-making and contemplation process, and the AI takes on the role of providing my experiences and knowledge.

Because my second brain provides my experiences and rules even without me explaining everything one by one.

This was really convenient, more than I thought. Tools like Obsidian exist, but the MCP server was much more useful in being specialized for collaboration with LLMs.

Closing

By making my development blog into an MCP server, the value of the blog has grown tremendously for me personally.

This is because it’s not just an organization post, but has become a vector DB of my personal experiences and a knowledge repository that the LLM refers to in real-time.

If Obsidian is a second external hard drive rather than a second brain, the MCP server has become a real second brain.

Of course, there are still many shortcomings and things to improve, and it should be considered that there may be incorrect information among the posts I’ve written. However, just from what I’ve experienced so far, I think building the MCP server was sufficiently valuable.

You Should Build One Too

My MCP server code is on GitHub.

The README has detailed installation and usage instructions, so please refer to it and turn your blog into a Second Brain too.

If you don’t have a blog, I think you should try starting one. Later, I think LLM platforms might provide these kinds of MCP Servers without having to make them yourself.

Thank you for reading this long post. I hope this post was helpful to you in some way. Thank you.